When most people think about land use planning, they picture zoning maps, bylaws, and maybe a heated council meeting where someone is fired up about parking - because their garage is packed to the rafters with skis, bikes, and holiday decorations, and now their truck is parked on the street.

What they don’t picture is a trail . . . but maybe they should.

Because trails - those winding ribbons of dirt, gravel, and the occasional surprise boardwalk, are some of the best examples of good land use we have. They connect people to place. They show what we value, and they quietly expose what’s not working in our built environment.

Trails Do What Planning Should Do

A great trail doesn’t just get you from Point A to Point B. It makes you want to go. It guides you, it feels natural without being wild, and somehow manages to be both useful, fun, and rad.

Wouldn’t it be nice if our communities worked the same way?

Let’s take a closer look. Let’s dig in.

What Trails Teach Us

Access + Accessibility

No car? No problem. Trails are one of the most democratic pieces of infrastructure we’ve got. No tickets, no gates, no dress code. Just show up and go. That’s land use equity in motion.

Of course, not every trail is equally accessible. Steep grades, rough surfaces, or missing connections can create real barriers for people with mobility challenges, families with strollers, or those without safe routes nearby, however, that is not a reason to give up. It is a reason design better, because when trails are thoughtfully planned, they do more than connect places. They connect people to possibility.

Trails give us access in every direction - outward and inward. They’re the bones of active transportation: a way to walk to the grocery store, bike to school, or take the long route home from work without ever touching a traffic light.

Trails also open the door to wild spaces. From front country to backcountry, trails make places feel possible, letting people reach lakes, viewpoints, and landscapes that would otherwise be out of reach.

Stewardship

Trails show what happens when people care and collaborate. The Sea to Sky Trail in BC wasn’t built by accident. It crosses First Nation, provincial, and municipal lands. It exists because people worked together instead of arguing over whose jurisdiction the dirt falls under. It's also part of the Trans Canada Trail1, linking the region to a country-wide network built on the same spirit of connection and cooperation.

That care doesn’t end once the trail is built. Long-distance routes like the Trans Canada Trail rely on ongoing stewardship across jurisdictions, communities, and generations, to keep them safe, accessible, and inspiring for all.

Place-Based Design

Good trails hug the land. They follow the contours, dodge the wetlands, weave through the trees. They’re designed for the place they’re in and not copied and pasted from somewhere else. Imagine if new subdivisions worked the same way.

Connection

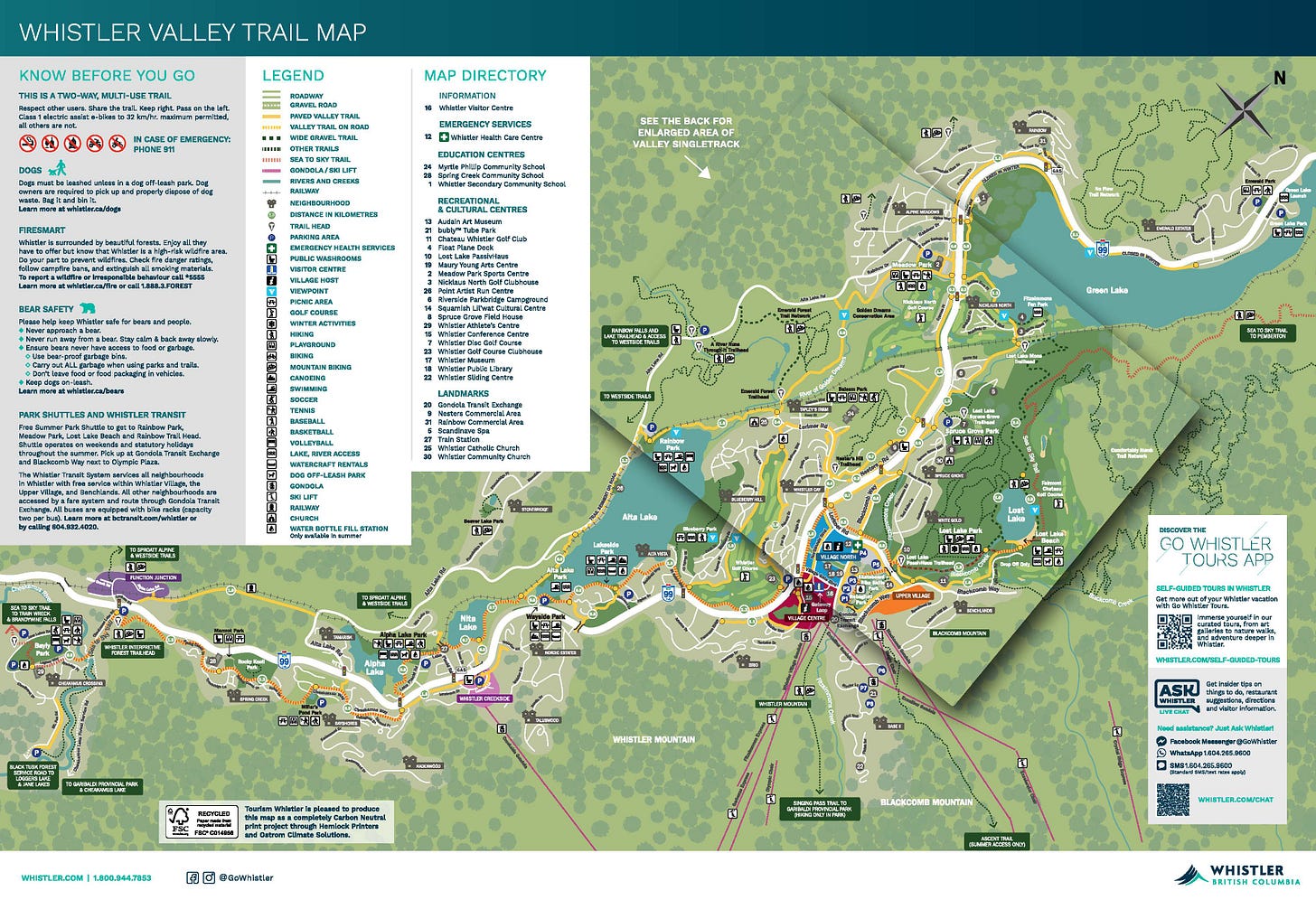

The best trails don’t just loop around in the woods like a lost hiker or my lost black & tan hound dog after she tracks a scent and ends up somewhere in the backcountry. Trails link up neighbourhoods, parks, schools, town centres, and nature. Vancouver’s Central Valley Greenway. Ottawa’s Rideau Canal Path. Whistler’s Valley Trail connects pretty much everything. Over on the Rock, as they say in Newfoundland, the T’Railway runs nearly 900 km across the island, turning an old railway into a multi-use lifeline from Port aux Basques all the way to St. John’s.

These aren’t just trails - they’re spines, and more importantly, they’re paced, multi-use pathways designed for walking, biking, strollers, skateboards, and sometimes even skis. They move at the speed of people, not vehicles.

Trails Are Invitations and Destinations

Some of my favourite memories didn’t happen at big events or fancy venues. They happened on trails.

Whether it was riding loam on the Sunshine Coast, doing a winery tour in Penticton, or a bachelor party in Bellingham that turned into a group ride (despite nonstop rain and even a bit of snow) the trail was the reason we showed up. Sure, we were there to celebrate something. But it was the shared motion, the flow, and the feeling of being outside together that made it memorable.

Not all trails are about getting somewhere. Some are about being somewhere.

Natural surface trails - think hiking, mountain biking, snowshoeing - aren’t just ways to move. They’re magnets. People will travel hours, even days, for a shot at the goods:

A mountain bike trip to Squamish

A hike through Fundy National Park

Snowshoeing around the ice caves on Lake Superior

A weekend loop on the Iceline Trail in Yoho National Park

These kinds of trails don’t just support recreation, they drive it. They bring business to rural communities. They build identity around landscapes. And they become part of people’s core memories.

If we’re serious about planning places people love, we can’t ignore the power of trails.

They’re economic engines. Social glue. And some of the most effective, underappreciated land use tools we’ve got.

Trails Reveal What Your Community Really Cares About

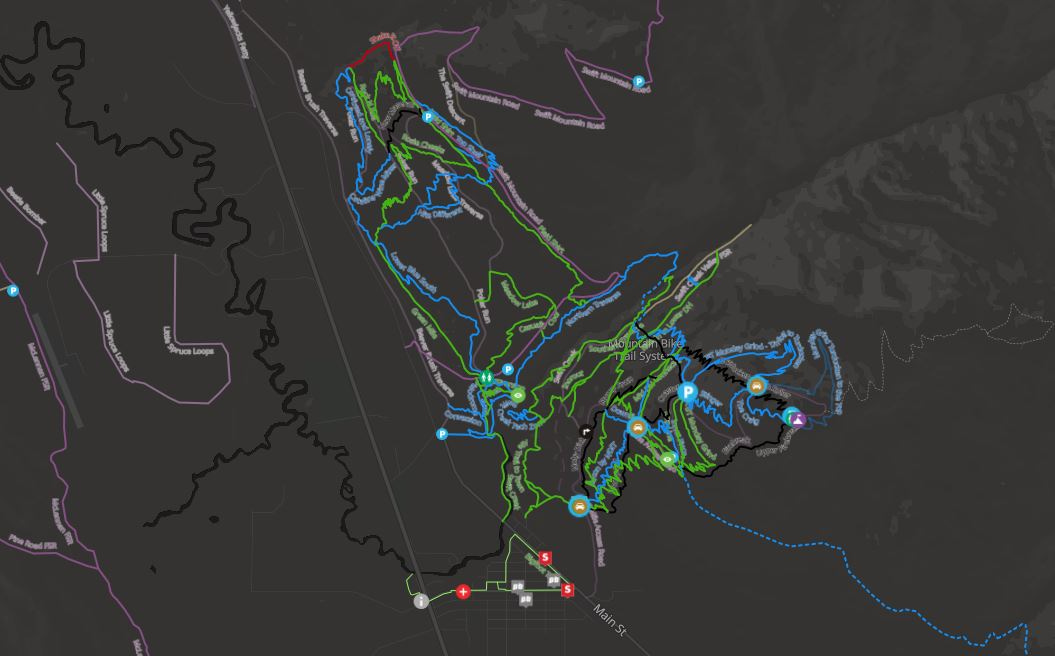

Grab a trail map, fire up Trailforks, or scroll through the Strava heatmap. You’ll learn more about a place from its trail network than any local government official community plan will ever tell.

Are the trails safe? Lit? Accessible?

Do they connect to schools or just dog parks?

Do they serve commuters or just the weekend warriors?

Are they cared for or crumbling?

Do they go where people actually want to go?

Trails quietly reveal who’s included and who’s forgotten, and in many places, they’re still treated like recreation, not transportation. That’s a missed opportunity and trails can and should do both.

Not All Trails Are On Land

In Canada, some of our most historic, scenic, and culturally significant routes are water trails. Canoe routes, portage networks, and paddle corridors that have been used for centuries.

From the French River in Ontario to the Bowron Lakes Circuit in BC, to the Athabasca River in Alberta which was once a vital fur trade route, and today it's a designated Canadian Heritage River2. Water trails connect us to landscapes in ways that are both ancient and immediate. They’re the original trade routes. The original tourism. The original trails.

Today, water trails still serve as powerful connectors by linking people to nature, communities to culture, and visitors to unforgettable experiences. They draw paddlers, anglers, and campers. They support Indigenous tourism, guide outfitters, and seasonal economies.

Some of these waterways are gaining formal recognition - not just as infrastructure, but as beings worth protecting.

In 2021, the Magpie River in Quebec was granted legal personhood3 through joint resolutions by the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit and the regional municipality of Minganie. The river was given nine specific rights, including the right to flow, to maintain its natural cycles, and to remain free from pollution.

It’s a reminder that trails, whether on land or water, aren’t just corridors. They’re living systems, and how we treat them reflects how we value the places they pass through.

Final Thought

So next time you’re out for a walk, on a ride, pushing that baby stroller, or paddling a kayak, think about what’s working.

That natural curve of the singletrack through the trees.

That seamless connection between a neighbourhood and nature.

The quiet glide along a river that’s been paddled for generations.

The fact that you’re moving, breathing, seeing people - not just passing through.

That’s not just a good trail. That’s good planning in action.

https://tctrail.ca/

https://www.chrs.ca/en

https://ecojurisprudence.org/initiatives/recognition-of-legal-personality-and-rights-of-the-magpie-river/